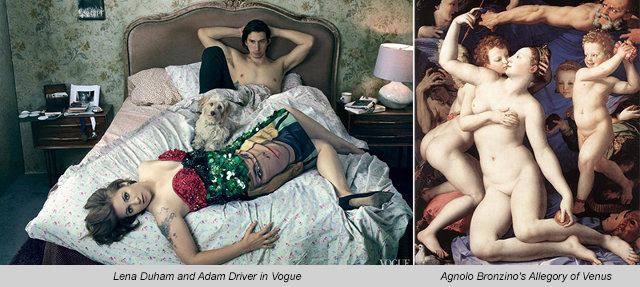

Recently, Vogue featured Girls star Lena Dunham in a controversial, Photoshopped spread by celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz. The feminist news site Jezebel swiftly offered $10,000 to anyone who could produce the untouched images.

They got them. Take a look, and you’ll find many of the usual fixes that photo editors make: lengthened limbs, nipped waistlines, thinned necks. However although such issues may be lining Twitter feeds and filling news columns nowadays in actual fact this kind of tweaking is pretty old…I mean it’s Michaelangelo-painting-the-Sistine-Chapel old!!!

Much of the history of art is the history of remolding women’s bodies to meet the same culturally sanctioned ideal, one that is as much about flattering privilege as it is about magically slimming waists.

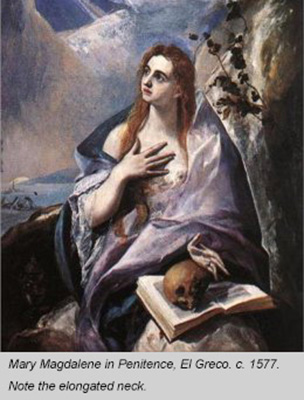

In the early 1500s, the period of High Renaissance art (in which artists valued anatomical accuracy) was winding down, and a new style of painting began to spread throughout Europe. Mannerism, as it was called, originated in Italy, and favored stylised renderings of the human form over more natural depictions.

As Ross Finocchio of The Metropolitan Museum of Art explains:

“Characteristics common to many Mannerist works include distortion of the human figure, a flattening of pictorial space, and a cultivated intellectual sophistication…the intense tones and gracefully choreographed figures…heighten the emotional pitch of the picture.”

Finocchio discusses an artist in the Medici court named Agnolo Bronzino, who adjusted the human form often to “highlight [the subject’s] learning and social status.” The 16th-century painter El Greco elongated legs and arms to create “highly charged and hypnotic” images.

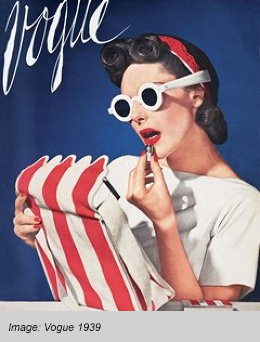

In 2012 The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York dedicated an exhibit to manipulated photography before the advent of Photoshop. Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop, showed how photographers in the 1800s would print several negatives onto one print, and apply additional pigment, to create images that were more vivid and that more closely mirrored the action we can see with the naked eye.

In 2012 The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York dedicated an exhibit to manipulated photography before the advent of Photoshop. Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop, showed how photographers in the 1800s would print several negatives onto one print, and apply additional pigment, to create images that were more vivid and that more closely mirrored the action we can see with the naked eye.

Stephen Frailey, chair of the photography department at the School of Visual Arts in New York, further remarked that,

“Most photography is fiction, and the whole industry of representation is based on artifice. The idea that we are going to replicate something plays into our sense of aspiration, and also into class. The figures being represented by Mannerist painters were of the ruling class. Of course they wanted to be represented in a particular way.”

Frailey also points out that fashion photography has always played tricks on viewers; darkroom techniques like dodging and burning, a technique that involves over- or under-exposing selected areas of the print, also let editors magically remove crow’s feet and chubby arms.

The point is to create a fantasy, as Dunham herself pointed out in a response to the whole who-ha over her Photoshopped images.

The point is to create a fantasy, as Dunham herself pointed out in a response to the whole who-ha over her Photoshopped images.

No one capitalizes on that fantasy more apparently than Annie Leibovitz, who has built her career photographing celebrities in wildly theatrical poses.

“Her work is very much about creating a persona for celebrities, in addition to the way that we know them,” Frailey says. “In other words [she’s] not just going to portray the celebrity at face value, but going to create an elaborate and stylized theater, which expands the narrative. It’s another piece of theater.”

And so the tradition of recasting the rich and powerful as fantasy depictions of themselves continues. On television, Dunham might be throwing reality in America’s face but in relation to art history, she’s just another member of the ruling class craving a more perfect version of herself.

ARTICLE SOURCED FROM: http://www.fastcodesign.com/